“I will go to an Ivy League university.”

I finished writing those words and looked back over the form. The top of the form read

“Basic Learning Skills — Career Goals Worksheet.”

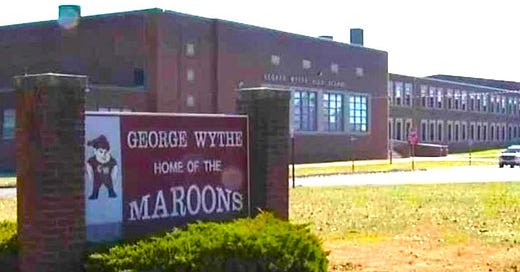

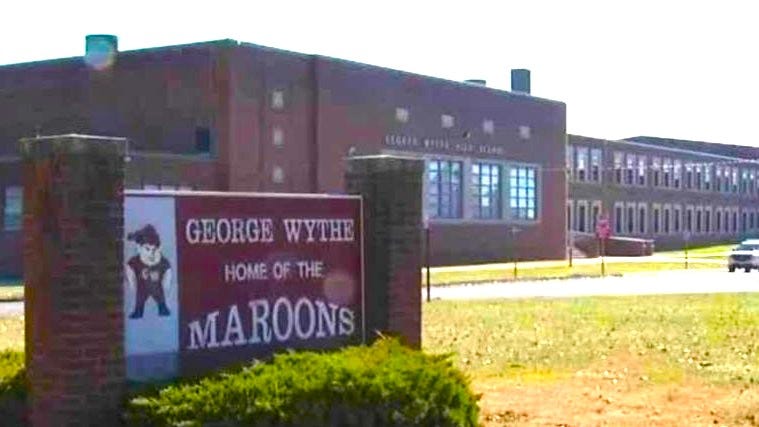

I was a dirt poor, Appalachian hillbilly in a class for academically challenged students, in a small high school firmly nestled in the middle of nowhere, and I had no idea what “Ivy League” actually meant.

I looked back over the words I had written. I erased “go to” and replaced it with “attend an.”

“I will attend an Ivy League university.” I said it out loud trying to make sure everyone in the class heard it. No one reacted.

“Looks about right.” I said — again — to no one in particular. I strutted to the front of the classroom, handed the paper to Mrs. Burgess, planted the form on her desk (less than a minute from when she had handed it to me) and said, “All done.”

Mrs. Burgess reviewed the page and stammered, “Ummm, Donald, you didn’t answer any of the questions. There are a lot of questions on this worksheet. You need to talk about your favorite work setting, the type of work you like to do, could you work in a factory, or do you want to be outdoors? You need to provide more information.”

“Yeah,” I responded. “I’m not going to do all that. I don’t really know what I want to do with my life yet. I’ll figure it out in college.”

The penciled eyebrows on Mrs. Burgess’ face arced in alarm. “Donald, you’re in this class, “Basic Learning Skills,” because you’re having trouble with your schoolwork. You’re just starting out now in high school. College … especially an Ivy League college … may not be realistic for you. You see, I am here to help you learn better techniques for studying, get better at schoolwork, and … hopefully … find career that is best suited for your … ummmm … aptitude.”

“Mrs. Burgess, I am not here, because I have trouble with schoolwork. I was in the honors class in middle school. I was on the Odyssey of the Mind team. I’m a nerd! I’m here, because I had trouble with Mrs. Allison! Mrs. Allison’s class was too easy, and I told her so. She didn’t change anything, and I got bored. So, I guess you could say that I filled my time with things she didn’t like.”

“I’m guessing your attitude is one of the things she didn’t like.” Mrs. Burgess smirked.

“You guess right! Same thing is probably going to happen in this class to be honest.” I scanned the room with the most judgmental look on my face that I could muster. My eyes landed back on Mrs. Burgess.

“Look, I shouldn’t be here.” I said. “But Mrs. Allison is punishing me for all the attitude I gave her. She got the Guidance Counselor to put me in here. She says I need to learn how to ‘stay focused in the classroom.’ So, here I am. Focused.” I stared directly into Mrs. Burgess’ eyes.

Mrs. Burgess paused to consider her next thought. She decided to choose her battles with this one. “Okay, Donald. Have a seat.”

So, I sat down, stared straight ahead, and stewed at the injustice of it all.

Although students called it an “LD” class, it was not truly meant for the “Learning Disabled.” We hadn’t received the medical diagnoses for such a designation. But we were sequestered in a building outside of the high school, and the words used by other students really were all that mattered. The stigma probably did more to hurt the students in that class than any remedial education it provided.

Especially for me! I did not belong in that class. “Basic Learning Skills” was just no place for …

… the smartest kid alive.

No. Really. That’s what I thought of myself. And it only got worse from there. Every year that went by convinced me more and more that no one could possibly be smarter than me.

And, to be fair, I had never met a kid smarter than me. Well, I probably had. Okay, fine, I definitely had met kids smarter than me … often. But I didn’t know it. Or, at least, I wouldn’t let myself know it.

And it wasn’t all my fault. So many people — teachers, students, the parents of students — they all told me over and over again just how smart I was.

“You are the best Quiz Bowl captain we’ve ever had.”

“You won the state debate championship. From George Wythe High School, no less!”

“Straight A’s. Drama Club. Chess. What can’t you do?”

I ate all of it up. I lived on it. I believed it.

Wrapped up in that arrogance was hope. There wasn’t much hope in my limited world of food stamps, secondhand clothes from the Goodwill, and two TV stations out of Roanoke. But — education? There was hope in an education. Especially an Ivy League education. Whatever that meant.

Even my parents said so. My parents were the byproducts of cyclical poverty and family dysfunction.

According to Dad, he got kicked out of George Wythe High School in the 8th grade and eventually joined the Army. Mom dropped out of Sugar Grove High School in the 10th Grade and later became a seamstress. God Bless ’em, they tried. But they couldn’t overcome the economic forces rattling Appalachia, the alcohol poisoning their bodies, and the depression throttling their souls — so they put their hope in education — my education.

“You won’t have to worry about this bullshit, when you’re a lawyer,” Dad once said to me through the Pall Mall Gold clutched between his teeth.

Mom, at least, would have the decency to wait for a pause between puffs before asking, “When you’re a lawyer, will you please get me out of here? I don’t need much. Just more than this.”

I heard similar thoughts from the community. They meant well, but the words stung.

“Especially with the parents you have, Donald, you’ve overcome so much.”

“How are you so smart with your upbringing? Most kids in your condition aren’t like this.”

“I bet you’re looking forward to the day when you can come back and save your family.”

Well, I was looking forward to that day, in fact. Hell, I was going to save the whole damn town. I just needed the education. An Ivy League education.

Despite all of my false intellectual bravado, I had not told anyone that I had designs on attending an Ivy League school. Even I knew the odds were long and why risk public rejection? Best keep that plan to myself, I thought, lest people think I might be the second or third smartest kid alive.

Plus, I already had a plan. William & Mary is an amazing public school in Virginia that is very similar to the Ivies in prestige, feel, and academic rigor. I was still pretty arrogant to assume that I could even get into William & Mary, but my two nerdiest best friends — Sam and Joey — had agreed to go to Williamsburg with me.

But as much as I loved the William & Mary plan, deep inside, I knew that I really wanted to make good on my promise (or was it a dare?) to Mrs. Burgess. I wanted to go to an Ivy League school.

I had not given it any real thought. I had no idea how much it would cost. I didn’t know what kind of degree I wanted. I just assumed an Ivy League education would make me a millionaire and solidify my place as the Smartest Kid Alive.

Unfortunately, there was a problem. The smartest kid alive did not know what the Ivy League was. As far as I knew, the Ivy League consisted of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. I did not know that it actually was an athletic conference. I had never heard of incredible Ivies like Brown, Dartmouth, or Penn. I did know that Columbia had the longest losing streak in football in America, but I had no idea it was a good school, much less an Ivy.

I also did not even consider other amazing schools like Stanford, Duke, Emory, or Vanderbilt. I was the most ignorant Smartest Kid Alive in the history of Smartest Kids Alive. Which meant— for better or worse — I was locked in on the Big Three.

But I didn’t know anything about Harvard, Yale, or Princeton, either. So, I did the only thing I could do in the early 90s, still a few years before the onslaught of the internet. I went to the library and pulled out the encyclopedia. I decided to use alphabetical order, so I pulled the volume for “H”….